“Teleportation is the transfer of matter from one point to another without traversing the physical space between them, similar to the concept apport, an earlier word used in the context of spiritualism.”

The concept of moving throughout the world freely without actually having to “physically” travel is the Holy Grail for many. Being able to explore a physical space that is thousands of miles away without having to deal with the rigors of travel seems like something out of a science fiction novel. With Street View, Google has brought us as close as we could possibly get to teleportation – without the actual physical matter transference, of course.

The project started as research at Stanford and then hopped into Google co-founder and CEO Larry Page’s car. Snapping photos of every nook and cranny of the planet so that people could travel the world from the comfort of their own homes or mobile devices is the hallmark of Google’s approach to the world around it and the evolution of technology.

I spent the day with the founding members of the Street View team to learn about how it went from a gimmick in someone’s mind to a utility that we use without thinking, and in some cases, wouldn’t want to live without.

Starting out as a camera strapped to Page’s car, Street View technology has been added to vans, cars, tripods, backpacks, bikes and even a snow mobile. It has become the eyes of all of Google’s vision for how we view the world after launching on May 25, 2007. While the product has had its fair share of controversy, Google has forged ahead.

GOING SOMEWHERE BEFORE YOU ACTUALLY GET THERE

Vincent told me a bit about the first concept of Street View, which was hatched at Google based on some experiments being done at Stanford, led by Marc Levoy. Levoy and one of his students had come up with a way to shoot video and paste it together into one picture, and Google decided to invest a little money into more experiments to see if it was feasible to take photos of every street in San Francisco. By parsing out this video frame by frame, it could make a really “long” image, or a facade of an entire street. It was distorted, of course, but this was the building block that Google needed to prove its Street View theory.Before I spoke with Luc Vincent, engineering director, andDaniel Filip, engineering manager, at Google Maps, I had done quite a bit of research into the history of the Google Maps product as a whole. What I didn’t know is how “pie in the sky” the concept of Street View actually was, which is an easy misconception to have once a technology has become so ubiquitous.

On these long, wiggly, very early street-wide images, Vincent said, “That was interesting to us.” Pretty to the point, and that was the moment that Street View was born.

After this testing, Larry Page strapped a camera onto his car and snapped shots throughout San Francisco. These images, along with some very basic cross-street data, would be patched together into something that wasn’t quite useful, but was even more “interesting,” as Vincent put it.

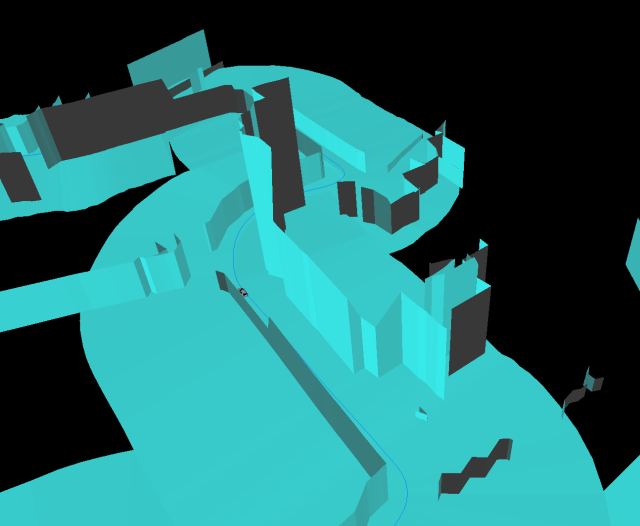

From Page’s car, the very early Street View team, which was comprised of a few random Googlers using their 20 percent time, threw some cameras into a van with a GPS and some lasers. The lasers were to grab data so that the team could know what the distance was between the camera and the facades of the buildings. That spacial recognition is what helps Google patch all of its images together and give it that 3D feel. The camera took a lot of pictures, the devices, hooked up to a raid of computers in the back of the van, and then this very unique dataset that is what makes Street View Street View, was amassed. It wasn’t pretty, though, as Vincent said:

It was a Frankenstein-looking car, but it let us capture enough data in the Bay Area. We had a van that we borrowed from the security team. It would go into the city, do some driving, and things would stop working and the computer gave us errors

.

GETTING BUY-IN

In Q3 of 2005, Vincent and his team gave a tech talk at Google, one that takes place every Friday, and was able to get more 20 percenters to join the team, including a key engineering VP. In October of 2005, Street View was approved and had the go-ahead to expand. There was no turning back. The world would be mapped out pixel by pixel by a bunch of moonshot thinkers who were trying to figure out how many devices they could bolt onto a car without it failing every five miles. While Street View was still under the radar at this point, Vincent could start hiring people – Filip being the first. The fact that these two are still working on the product today is a testament to how far it’s come and how much is still left to do.Working on a project at Google with your 20 percent time is only part of the battle. Getting other people to join your team and getting it approved is a whole separate hurdle. Vincent told me that once they collected all of this data, people started piecing it together, and the demos made sense.

In early 2006, there were seven Googlers working on Street View full time, with the goal of making it a “real product.” Vincent had this to say on the transition:

There were a few things at that time that we were really interested in. Perspective panoramas were cool but really hard to make. We only had one UI/UX guy to figure out how to integrate it into maps, but there was no compelling way to show it, because there was no “Google Maps” when we started.

Yes, all of the infrastructure that you see today in the Google Maps product didn’t even exist at that time, so the Street View team at Google had even passed Google’s current plans and trajectory. Vincent shared:

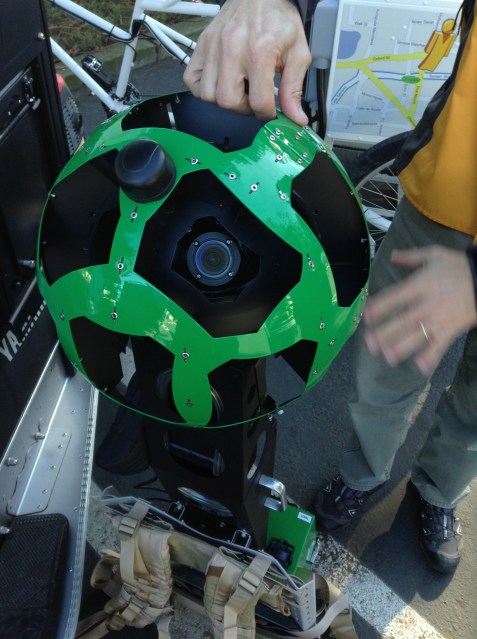

What we did was built a new platform. We wanted to build something reliable and scalable and put it in a car. Something with high-speed cameras to take pictures, so we had 8 SLRs in a rosette configuration to take images all around the vehicle. Our thought at this time was “it was going to have to be expensive to be comprehensive.”

This “rosette design,” which originally consisted of five lenses and one main fisheye called the L2, has become the core to every Street View vehicle. Once this approach to photography and information-gathering was set in stone, Google knew that this would work.

THE DATA

Street View collects quite a bit of data. Vincent’s team had to figure out a way to scale these original vans to grab as much of it as possible so that they wouldn’t have to drive the same routes more than once. The team threw lasers onto the vans – four on each side – to get distance information, more GPS, collected wind velocity and everything in between. He said that the approach was simple: “Collect as much data as possible and figure it out.”Google Street View, and everything Google does pretty much, is all about the data it collects. In many ways, Google is extremely obsessed about collecting all types of data. This approach has ruffled the feathers of those who feel like their privacy is being invaded, but the company takes the approach of “collect as much as you can, make sense of it later, display it in a way that helps people.” Take that approach, then rinse and repeat.How was this going to work outside of San Francisco, though? There is now Street View data from more than 3,000 cities and 47 countries all over the world, so there was a lot of work ahead before this project ever saw the light of day.

Vincent said:

We had a rack of four or five machines in the back of the vehicles, but something was always breaking. We built three or four of these, and took images mostly in California. The cars were always failing, so we couldn’t scale this.

Five million unique miles driven later, the failures are now few and far between.

MAKING SENSE OF THE DATA

All of this sounds fantastic – collecting data and photos just by driving around a city – but to make it actually useful, the team had to come up with a way to visualize it and tweak it from a user-experience perspective. Ones and zeros make uber-math geeks happy, but there’s no way that our parents could ever make sense of any of that. To fully experience Google Maps and Street View, the design had to be nearly perfect, as if you just stepped into a foreign city for the first time and had your head on a swivel.

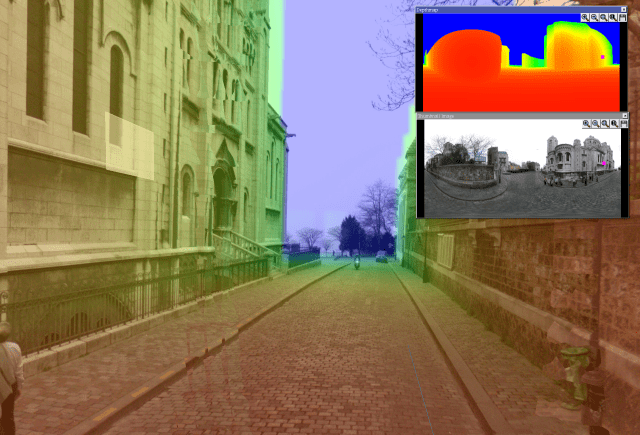

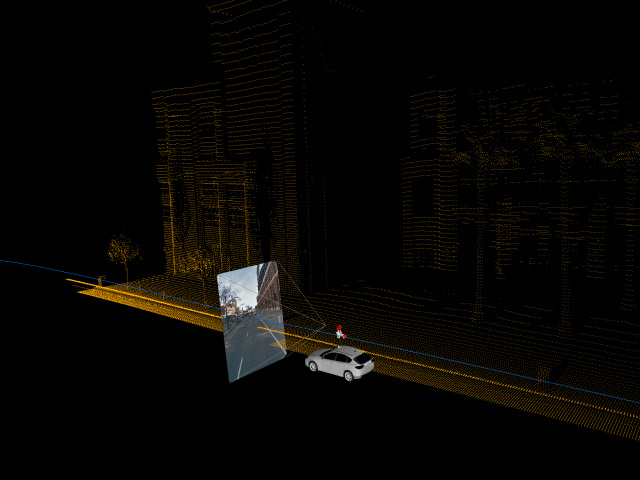

To do this, the Street View team built itself an internal tool to churn through all of the geographical information: they smacked layers of photos on top of it, used all of the spacial details picked up by the lasers bouncing off of buildings and landmarks, and then determined whether it was actually usable. With quite a bit of work, it finally was:

This data was collected by drivers who would fill up hard drives and ship them back to Google. The drivers wouldn’t send them in until they had five disks completely full. The disks would get shipped to a data center, the information uploaded and then everything would get fed into its core database and go through a few processing steps.

One of those processing steps was the blurring of people’s faces and license plates. These are seemingly obvious privacy issues that nobody thought of before this product existed, so Google had to invent the technology to do it systematically. Additionally, there are 15 images taken for each finished shot and angle that you see on Street View today, and Google’s software takes all of these images and mashes them together, adjusts the exposure for sun, shadows, color differences and brightness. That’s the processing that goes into making “perfect” panoramic images.

All the while, Google is detecting and extracting information from objects like street signs to feed back into the main Google Maps product. That’s quite a load.

As each of the cameras on top of the vehicle would snap pictures, the location information could be associated with it, along with that spacial information from the layers, thus allowing the Street View team to stitch together all of the angles necessary to create this beautiful panoramic imagery.

A photo from the front, sides, behind and then eventually from the fisheye looking upwards at buildings would turn into the 3D views that we enjoy today:

One cool thing that I learned was that since the cameras looking in front of and behind the vehicle were partially obstructed, Google invented a technology to smooth those images out using shots from other angles, and that’s why the 3D images seem as if a photo-taking vehicle never existed:

THE LAUNCH AND STREET VIEW TODAY

It was an immediate success, even though the Street View team, and Google, didn’t know how well it would be received. Of course, Google was ready to burn a few machines to the ground by serving up this imagery, and Vincent recalled what that day felt like:Google Street View launched officially in 2007 and was only available for San Francisco, New York, Las Vegas, Miami and Denver. The cameras at that time were 5 megapixels, which is barely what we have on our phones today. Now they’re 75 megapixels; try to wrap your brain around that one.

We saw traffic go through the roof and about as high as we could serve, well we hit that limit immediately. What’s great about being at Google is you get to observe traffic and interest. The launch showed the interest, and a bunch of websites started popping up and sites popped up showing funny images captured by us.

Those funny, and sometimes disturbing, images have since caused a stir, with Google having to defend itself in some cases.

The original vans weren’t scalable, so fitting this technology, which now consists of “ladybug” cameras with those same 8 lenses and a fisheye, had to be put into cars that could be driven everywhere in the world. You’ve probably even seen one by now.

“It took some time to get there,” Vincent says of Street View, as all of its contraptions have gone through multiple iterations, leading up to Google eventually building its own cameras and custom rigs. Once the core technology was solid, Street View was being asked for in smaller cities and towns in other countries, so the team scaled down the rigs to fit onto other vehicles like bikes. The Street View Trike can maneuver its way in and out of alleyways, around big landmarks and down streets that aren’t wide enough for a car or van.The original vans weren’t scalable, so fitting this technology, which now consists of “ladybug” cameras with those same 8 lenses and a fisheye, had to be put into cars that could be driven everywhere in the world. You’ve probably even seen one by now.

Then, a member of the team decided that he wanted to do the Street View treatment on the mountains during the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver. Why not, right? The Street View technology was then adapted to be driven around by a snow mobile. It was too cold out for the camera, so Vincent said that the engineer had to take off his jacket to keep it warm. As more data was collected and more imagery was displayed online, the ideas came faster and faster.

Then, a member of the team decided that he wanted to do the Street View treatment on the mountains during the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver. Why not, right? The Street View technology was then adapted to be driven around by a snow mobile. It was too cold out for the camera, so Vincent said that the engineer had to take off his jacket to keep it warm. As more data was collected and more imagery was displayed online, the ideas came faster and faster.

We made a new mini computer and shrunk everything and put it onto a pushcart to go into large indoor spaces. A tripod would be too time consuming. The challenge is that there is no GPS indoors, so we worked on complex algorithms that extracts locations of the Trolley without GPS, with lasers and positional data. This Trolley has now helped launched 50 museums.Why would you stop with outside imagery? Why not get panoramic imagery indoors, especially in famous museums? The Street View Trolley was born. On indoor Street View, Vincent said:

You’re starting to get the picture. If it doesn’t exist, that doesn’t stop forward-thinking Googlers. Once something works just a little bit and it seems cool and useful for consumers, the money and resources are allocated and things are built on the fly by any means necessary.

You’re starting to get the picture. If it doesn’t exist, that doesn’t stop forward-thinking Googlers. Once something works just a little bit and it seems cool and useful for consumers, the money and resources are allocated and things are built on the fly by any means necessary.

The current Street View cameras currently consist of 15 cameras (no more fisheye needed), because Vincent felt like Street View wasn’t getting enough photos. Google continues to push the limits of quality and accuracy, which is one of the reasons why Apple had such a hard time launching its own Map product. You see, Google has been doing all of this since 2005. Not only that, it has been doing it at a huge scale since 2007. All of those lessons learned, all of that data and all of those man-hours mean that Google not only had a head-start, but also a perennial edge moving forward. Basically, catch them if you can.

The current Street View cameras currently consist of 15 cameras (no more fisheye needed), because Vincent felt like Street View wasn’t getting enough photos. Google continues to push the limits of quality and accuracy, which is one of the reasons why Apple had such a hard time launching its own Map product. You see, Google has been doing all of this since 2005. Not only that, it has been doing it at a huge scale since 2007. All of those lessons learned, all of that data and all of those man-hours mean that Google not only had a head-start, but also a perennial edge moving forward. Basically, catch them if you can.

At the end of my day with the Street View crew, I asked Vincent why he started all of this. His answer, straight-faced, serious and yet wide-eyed and empathetic…”We wanted to connect people.”

MAKING COMPLEX THINGS COMMON

Yes, a lot of Google’s technology runs in the background of our desktops and phones without any of us knowing how it works. That’s the magic, though; you don’t really want to know how the sausage is made; you just want to know that it tastes really good. When something tastes good, you’ll come back and eat more and even tell your friends about it. Vincent likes that Google products are taken for granted, because it allows them to innovate more – and faster.

There are a lot of things that Street View can accomplish in the future. With its Trekker backpack, wooded areas can be charted out to help crews look for missing people, as well as allow you todiscover the Grand Canyon without ever actually getting on a plane or bus.

Even though the early days of Street View weren’t pretty, be it the devices that were cobbled together or the artifact-full images that were posted, people got the concept, embraced the concept and asked for more. As long as Google keeps trekking along to gather as much data as it can and figure out how to display it later, we’ll continuously be introduced to more products that just work.

Even though the early days of Street View weren’t pretty, be it the devices that were cobbled together or the artifact-full images that were posted, people got the concept, embraced the concept and asked for more. As long as Google keeps trekking along to gather as much data as it can and figure out how to display it later, we’ll continuously be introduced to more products that just work.

While you might not be able to physically teleport just yet, your mind can wander wherever you like, making the world feel like a smaller place. That connects us to people in a way that no other technology has ever accomplished.

The best part about all of Street View’s historical body of work is that a lot of these approaches have been open-sourced, as if to say “come and get us.” Can you catch up to Google? When it comes to Maps, you better have a pretty sophisticated and fast vehicle, because they’re literally everywhere; just look for the iconic camera.

Also, when you use your smartphone to scope out an area of interest, remember everything that went into displaying that smooth imagery so quickly. Who knows, you might be able to participate in the project one day. With Google Glass, you might be able to take shots of the world around you and have them included in Street View imagery.

Sounds crazy, doesn’t it? About as crazy as strapping a digital camera onto a founder’s car.

No comments:

Post a Comment