The Office 365 service was first released two years ago. It was an effort to stem the tide of Google Apps and other Web-hosted alternatives to Microsoft’s on-premises and privately hosted Exchange and SharePoint products. They were simplified versions of their perpetually licensed namesakes: designed to run in Microsoft’s Azure cloud service, based on the same core technology, but substantially different in terms of how they were managed and deployed.Today, Microsoft flips the switch on the latest generation of its Office 365 Enterprise hosted collaboration service. At the same time, Microsoft will release for purchase the software products that make up Office 365—Office 2013 Professional, Exchange 2013, SharePoint 2013, and Lync 2013.Combined with Web versions of Office applications, Office 365 has been both more and less than its Google Apps competition. It blends perfectly with Microsoft’s desktop Office tools and even comes with Office 2013 Pro Plus licenses in its $20-a-month “Plan E3” form. But Office 365’s strengths are less impressive when you look at how it trails Google’s live collaboration and social features. For full disclosure, Ars is an Office 365 shop—but we use Google Docs, GTalk, and a number of other Google Apps tools to fill in gaps we perceive in Office 365.

That may change with the latest incarnation of Office 365 and the Exchange and SharePoint platforms. The differences between Microsoft’s hosted versions of Exchange and SharePoint and the on-premises counterparts have virtually disappeared. Office 365 has gained some real enterprise-strength management features like data loss prevention and e-discovery (at least in its premium plans). And the on-premises versions of the core of Office 365—Exchange Server 2013, SharePoint 2013, and Lync Server 2013 (which will be reviewed separately by Peter Bright)—have all been tweaked for better use in a virtualized world. Regardless of whether you buy a perpetual license and install Exchange and SharePoint on a server in your LAN closet or data center, set up a hosted mail service with a service provider, or subscribe to Office 365 Enterprise, you'll have essentially the same set of administrative tools and the same user and administrative experience.

But perhaps most importantly, the latest versions of the Exchange and SharePoint platforms strike an important balance. The IT department has the power to tightly manage how information flows into, out of, and through an organization, but the platforms also give users the ability to wing it. The new Office 365, Exchange, and SharePoint allows users to collaborate socially, to build ad-hoc solutions, and to self-provision new features and applications through both public and private “app stores” (depending on how much leash the company wants to give them).

We set out to determine just how well the new service and servers strike this balance. We tested on a local installation of Exchange and SharePoint, then used an Office 365 implementation of the same services among Ars colleagues—as well as a known bad actor we’ll call Packetrat, who was out to break the rules.

Exchange 2013 and Exchange Online

There are a number of things Exchange 2013 changes from the user perspective, both for on-premise and in Office 2013. Even if you’re not using Outlook 2013 as your mail client, there are elements of Exchange that will change how you interact with your inbox—even how you think of an inbox.Most of what users will notice is centered on what shows up in their mailboxes. Now, it’s not just mail. Exchange 2013 and Exchange Online offer more than shared folders and SharePoint integration; there’s a whole new model for in-mailbox applications hosted on the Exchange server.

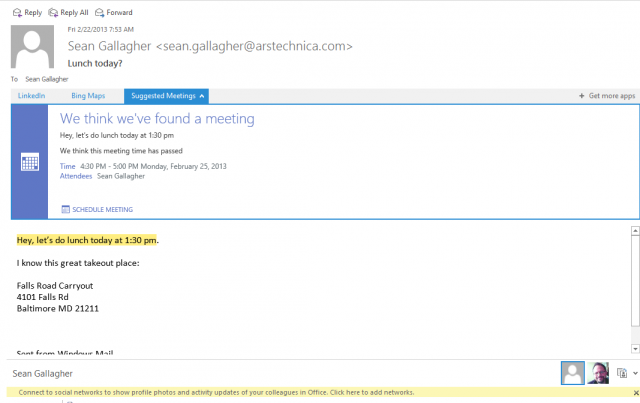

Enlarge / The Suggested Meeting app in Outlook finds a time in an e-mail and suggests a calendar entry automatically.

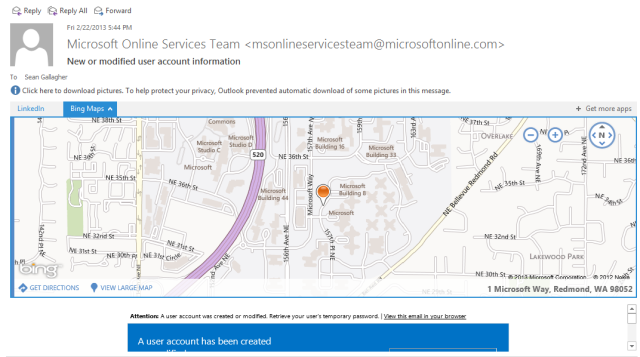

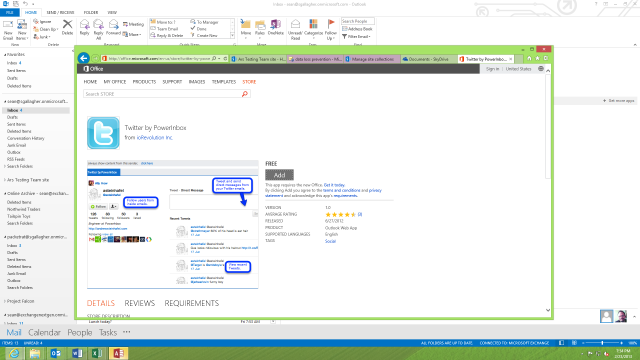

Called “Apps for Outlook,” these HTML and JavaScript based applets are exposed within e-mail messages in the Outlook 2013 client as well as the new Outlook Web Access Web client. The apps detect content patterns in e-mail messages and other content, then retrieve data from Web services based on that data. Exchange comes with three installed by default—a Bing Maps tool, an “action items” finder that flags e-mails for follow-up, and an appointment suggestion applet. Each of these looks for content patterns in messages (addresses for maps, dates and times for appointments) to generate their content. A number of other applications are already available through Microsoft’s Office website, including ones that tie in services such as LinkedIn and Twitter.

Enlarge / The Bing Maps application, in Outlook Web Access, finds an address and offers to show you where it is.

Which apps show up in Outlook are determined by the Exchange administrator, but there is a growing collection of free and paid applications available through the Office website (directly accessible through the administrative interface). And internal developers can build their own apps for deployment through Exchange as well, adding them either by pulling them in as a file or pointing to their URL. Developers can build mailbox apps using Microsoft’s “Napa” Web-based developer tool for Office 365 and then share its URL to be used on any Exchange server. Once an application is added, it’s available to everyone as an option unless it’s disabled. If desired, apps can be made mandatory as well.

Enlarge / Office.com's Apps for Outlook app store includes apps for Twitter, LinkedIn, and other services.

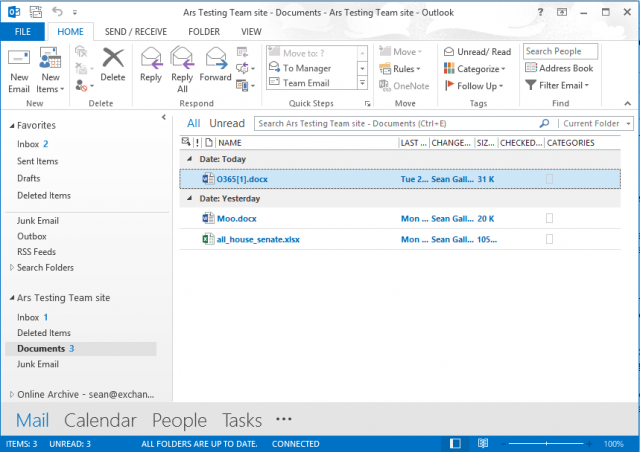

There’s also more integration with SharePoint through a new feature called Site Mailboxes. You can configure a mailbox that’s associated with a specific SharePoint “team page” or other collection within the collaboration server. That mailbox includes an e-mail address that people can send messages to as well as access to the documents in the site’s library. (Those documents are accessible directly from within the Outlook client, though not through Outlook Web Access). Lync Server 2013 also integrates into the Exchange mailbox. It can archive chat sessions in the mailbox store and store Lync contacts there as well.

Enlarge / A view of a SharePoint Team site mailbox, with its shared documents, in Outlook.

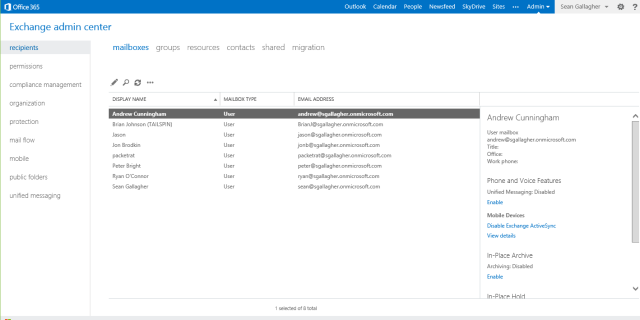

The other changes in Exchange may be subtler to users, but they’ll be immediately apparent to administrators. If you’re installing Exchange 2013 locally, the first thing administrators will notice is what's gone: the Exchange Management Console and Exchange Control Panel management interfaces. They’ve been replaced by Exchange Administration Center (EAC), a Web-based administrative console shared across all the versions of the Exchange platform. This is the same interface administrators use for Exchange Online, the cloud tenant version offered on its own or as part of Office 365.

Enlarge / The Exchange Admin Center, the new Web-based console for managing Exchange 2013 and Exchange Online.

There's still support for PowerShell-based administration commandlets (both for on-site and Online versions of Exchange), so automated provisioning and scripted administration of Exchange servers is as powerful, so to speak, as ever. But as far as day-to-day administrative tasks go, it's all done from a browser. This is the case regardless of whether your Exchange server is under your desk, in a rack in your own data center, running as a hosted instance with a service provider, or a tenant in the Office 365 cloud.

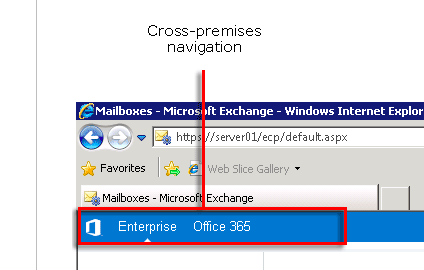

EAC also integrates management across both on-premises and hosted services for companies that opt for a “hybrid” Exchange deployment, allowing administrators to move from Enterprise to Office 365 tenant management with a single click in the header.

An EAC console administering both an on-premises Exchange 2013 Enterprise install and an Office 365 tenant allows navigation from local to cloud with a click on the tab.

Another thing missing from the new Exchange is support for older versions of the Outlook client. Exchange 2013 requires its Outlook clients support auto-discovery of the server; this is in part to help streamline cloud deployments of Exchange. Clients also have to support “Outlook Anywhere” access—remote procedure calls via HTTP—to connect to Exchange 2013 instead of using TCP-based RPCs as in older versions of Exchange. In theory, it’s a good thing—unless you have clients still running Outlook 2003.

Those changes are in part because of a major architectural shift in Exchange. Functionality used to be split across multiple server elements to allow for better scaling out of Exchange. Now it's been consolidated into two components: the Mailbox server and the Client Access server. The Mailbox server handles all of the heavy lifting, including the mailbox database, mail transport services, and unified messaging and client access protocols. The Client Access server role, on the other hand, is lightweight. It's intended to act as a proxy and allow for load-balancing of connections. It also handles incoming requests from HTTP, POP, IMAP and SMTP.

The result is that it’s a lot simpler to deploy Exchange in larger organizations. Servers no longer need to have a fully qualified domain name for clients to connect to them; you can have load-balancers pass connections to whichever Client Access server is available. There’s less need for configuring namespaces for different services; whole rafts of Client Access servers can be hidden behind a small number of host names.

EAC might seem like a downgrade for some administrators. There were a number of things you could do from the MMC-based Management Console that you now have to rely on PowerShell to do. But the EAC is an upgrade for those already using Office 365, with more administrative and reporting features exposed. Two of those features are compliance and policy management tools new to Exchange as well. However, they’re exclusive to the Enterprise version of the on-premises server and the enterprise-level plans of Office 365: data loss protection and e-discovery.

Exchange had data retention policies for some time. But the new e-discovery features make it a lot easier to find content in mailboxes—or in Lync instant messages or SharePoint sites—that needs to be held and prevent it from being deleted. All you need is the right query to find it. SharePoint 2013 also has its own e-discovery capability for content not explicitly connected to Exchange.

Exchanges’ e-discovery tools allow for “in-place” preservation of content that matches up with a specific keyword within a group of mailboxes—usually someone working on a specific team requiring regulatory oversight. The e-discovery tool allows any matching e-mail or other messages (including voicemails and other content stored in the Mailbox server) to be retained either indefinitely or for a set period of time based on the needs of the company

Read The Complete Review @ ArsTechnica

No comments:

Post a Comment